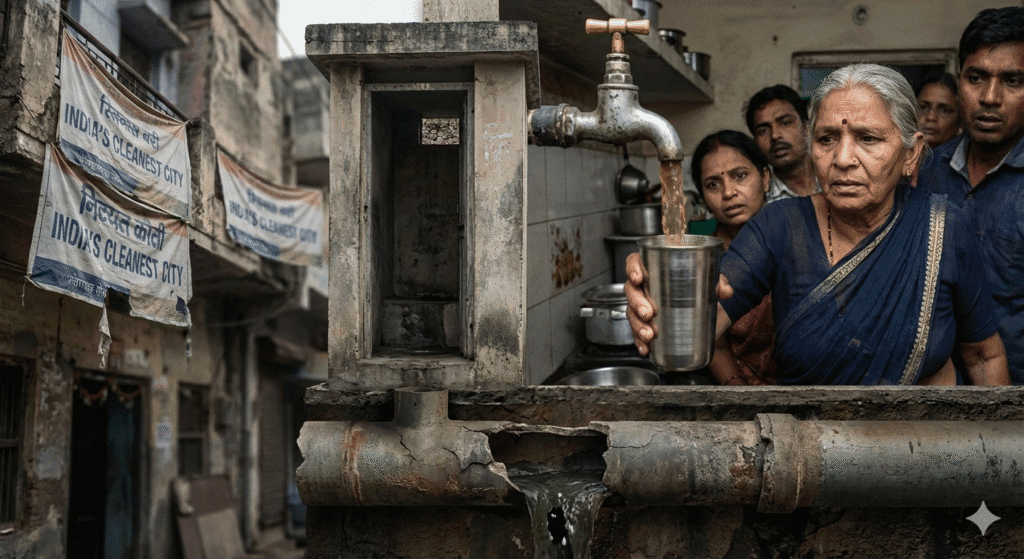

Indore’s Water Tragedy: How “India’s Cleanest City” Failed Its People

Indore, India’s much‑celebrated “cleanest city” for eight years in a row, recently it is at the centre of a deadly water scandal. In late December 2025, a severe waterborne disease outbreak in the Bhagirathpura area killed at least 10 people and sickened more than 1,400 residents. The trigger was brutally simple and utterly preventable: sew

age from a public toilet, built directly above a fractured Narmada drinking water pipeline, leaked into the city’s tap water. The contamination carried dangerous pathogens including Vibrio cholerae, E. coli, Shigella and Klebsiella, exposing how fragile Indore’s celebrated sanitation model really is.

WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED?

Lab tests confirmed that the outbreak was caused by contaminated drinking water, not a seasonal bug or isolated food poisoning. Officially, at least four deaths have been directly linked to the polluted water, but the city’s mayor admitted to 10 deaths, and local reports put the toll even higher, at 13–14. Among the dead is a six‑month‑old baby whose formula was mixed with tap water.

Hospitals across Indore reported a surge of patients from Bhagirathpura with vomiting, severe diarrhoea, fever and dehydration. Between 116 and 200 people were admitted to 27 hospitals, while over 1,400 residents reported gastrointestinal symptoms. Health teams fanned out across the neighbourhood, surveying more than 2,700 households, checking around 12,000 people and treating over 1,100 on the spot for mild to moderate illness.

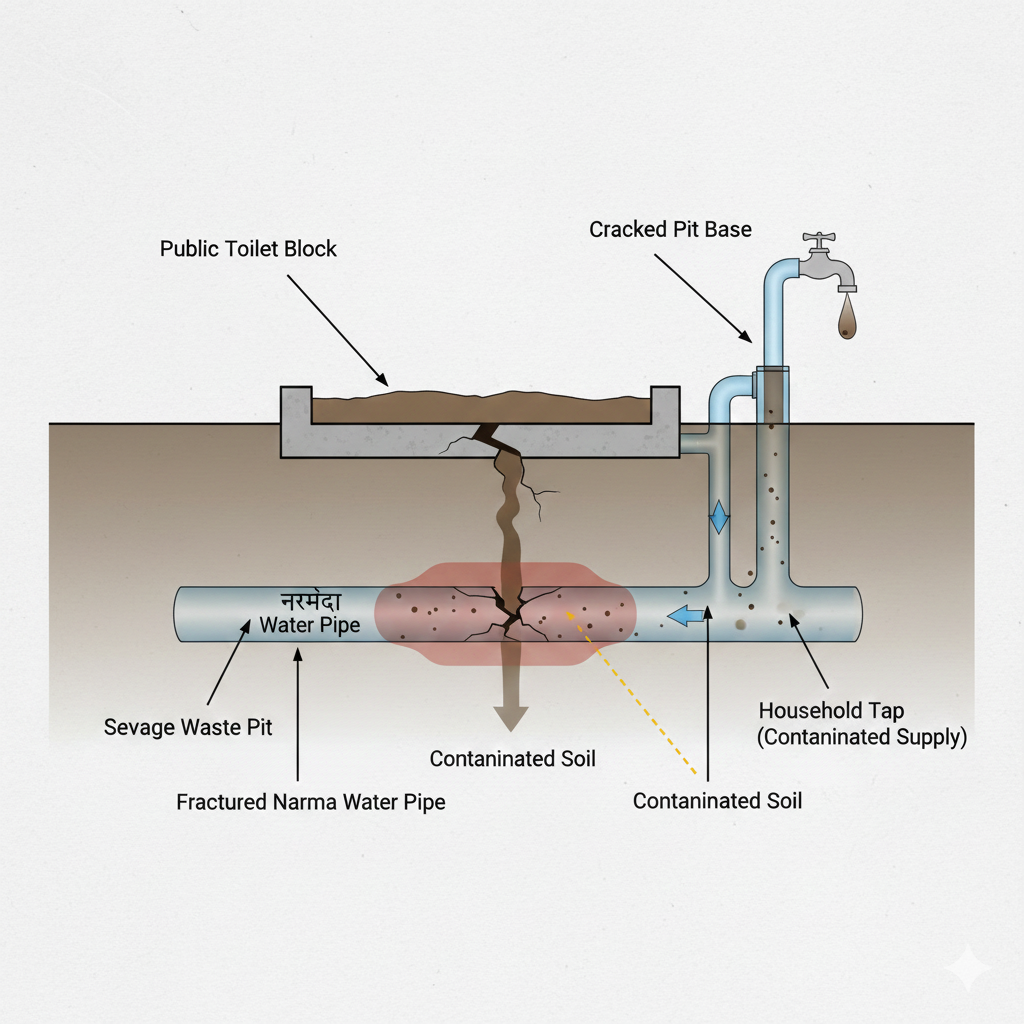

HOW DID SEWAGE ENTER DRINKING WATER?

At the core of this disaster was a staggering design and planning failure. A public toilet at a police chowki in Bhagirathpura had been constructed directly above a major Narmada water pipeline — and crucially, without the required safety tank. The toilet’s drainage emptied into a waste pit that sat right over a cracked section of the main water line. Over time, sewage from that pit seeped into the fractured pipe, effectively turning tap water into a carrier of fecal bacteria.

This did not happen in some neglected town with no planning; it happened in a city that proudly holds a “Water Plus City” certificate, which is supposed to guarantee that all wastewater is treated and that no untreated sewage enters the environment. The reality under that toilet belied the glossy certificates.

THE WARNINGS NO ONE ACTED ON

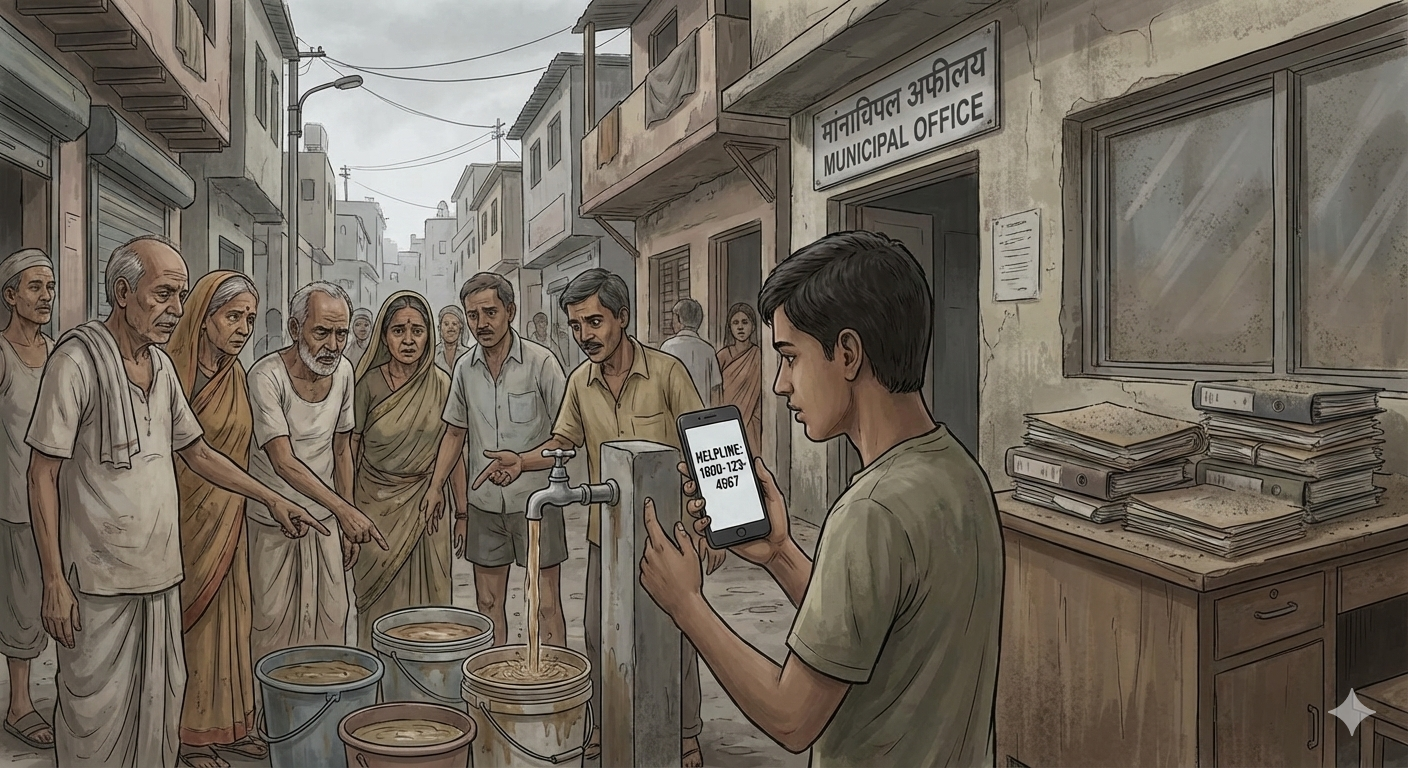

The crisis was years in the making. Residents of Bhagirathpura had been complaining about poor water quality since at least 2024. In August 2024, the Municipal Corporation even floated a tender to replace the ageing pipeline. That tender then sat idle, unopened for months, reportedly stuck in bureaucratic and funding delays under the AMRUT Urban Mission. It was only re‑issued around July–August 2025, with documents openly noting complaints of foul‑smelling, dirty water.

On the ground, the warnings got louder:

- 15 October 2025: A distress call about contaminated water was logged on the mayor’s public helpline.

- Mid‑November: A resident formally complained of “acid in the dirty water.”

- 18 December: People reported a foul stench in their Narmada water supply.

- 25 December: Residents noticed bitter taste and visible discoloration in tap water.

Yet, water continued to flow through the same compromised pipeline. By 27–28 December, the first wave of serious illness hit. Only on 29 December, after the first deaths, did the administration move into urgent response mode.

A telling detail: the work order to finally replace the pipeline was issued on 26 December 2025 — just as people were already falling seriously ill. The city had known the infrastructure was failing; it simply acted too late.

GOVERNMENT RESPONSE: SWIFT NOW, SLOW BEFORE

Once the crisis became impossible to ignore, the State Government did move quickly.

- Hospital capacity was ramped up, including a dedicated 100‑bed ward at MY Hospital.

- Four ambulances, over a dozen doctors and two dozen health workers were deployed door‑to‑door in Bhagirathpura.

- The contaminated pipeline was shut, repaired and disinfected; the offending toilet was dismantled.

- Water tankers were sent in, and residents were told to boil water for at least 10 minutes before drinking.

- The Chief Minister announced ₹2 lakh compensation for each death and promised that the government would bear all treatment costs in both government and private hospitals.

A three‑member inquiry committee headed by senior bureaucrat Navjeevan Panwar was set up to probe the failure. The National Human Rights Commission also stepped in, issuing a notice to the Madhya Pradesh government after reports that residents’ complaints were ignored for days.

Some officials were punished: a zonal officer and an assistant engineer were suspended, and the sub‑engineer in charge was sacked. But questions over political accountability linger. Urban Development Minister Kailash Vijayvargiya, who represents the area, initially tried to suggest that some of the deaths were due to “natural causes,” blurring the line between contamination‑related deaths and others — a move widely seen as downplaying the scale of failure.

AN “INFRASTRUCTURAL NIGHTMARE” BEHIND A CLEAN IMAGE

Local officials themselves have described Bhagirathpura as an “infrastructural nightmare” — a dense, low‑income settlement criss‑crossed by 30‑year‑old, unplanned water and sewage lines with poor separation and very limited maintenance. Around 60% of the local pipeline network had reportedly been upgraded in recent years, but repeated warnings to replace the remaining 40% were ignored.

This points to a deeper pattern:

- DEFERRED MAINTENANCE: Ageing, hidden infrastructure was allowed to run far beyond its safe life.

- ADMINISTRATIVE INERTIA: Tenders floated, then left to gather dust; work approved only after disaster struck.

- IGNORED VOICES: Repeated complaints from residents — mainly poor and working‑class — were not treated as urgent.

- AWARD‑DRIVEN GOVERNANCE: Energy went into winning cleanliness rankings and water certifications, while basic, invisible risks remained unaddressed.

THE AWARDS–REALITY GAP

Indore’s story exposes an uncomfortable truth: city rankings and certificates do not always reflect the lived reality of all residents. The same city that was feted nationally for:

- Treating 100% of its wastewater,

- Preventing untreated sewage from flowing into rivers,

- Reusing treated water, and

- “Effectively managing” its water resources.

A major drinking water line running beneath a public toilet with no safety safeguards. That design would be considered reckless anywhere — let alone in a city showcased as a model of urban cleanliness.

This raises hard questions about how such awards are assessed:

- Are inspections deep enough, or are they focused on visible, easily demonstrable metrics like public toilets, street sweeping and solid waste management?

- Are poorer, peripheral neighbourhoods like Bhagirathpura properly audited?

- How much weight is given to continuous testing of drinking water and to responsive grievance redressal?

LESSONS FOR INDIAN CITIES

The Indore water tragedy is more than a local scandal; it is a warning for every rapidly growing Indian city.

- INFRASTRUCTURE MUST COME BEFORE IMAGE – Awards and rankings cannot substitute for continuous investment in basic water and sewage systems, especially in older, congested areas.

- COMPLAINTS ARE AN EARLY WARNING SYSTEM – When entire neighbourhoods report foul‑smelling or discoloured water, the default response must be to investigate and, if needed, stop supply — not to wait for lab results after people fall sick.

- EQUITY MATTERS – If low‑income areas consistently get delayed maintenance and slower responses, cities will remain vulnerable to precisely these kinds of concentrated disasters.

- TRANSPARENT CASUALTY AND DATA REPORTING IS ESSENTIAL – Confusion over whether the death toll is four, ten or fourteen undermines trust and obscures the true human cost.

- CERTIFICATIONS MUST BE GROUNDED IN REALITY – Any cleanliness or “water plus” label should be contingent on regular, independent audits, public disclosure of water testing data, and community‑level verification.

Indore’s tragedy shows how, beneath a polished surface, neglected pipes and ignored complaints can turn tap water into a killer. For India’s cities, the message is clear: it is not enough to be the “cleanest” — you have to be safe, especially where people can’t see.

About the Author

Support Vijay Foundation

If you value independent analysis and public-interest work on technology and privacy, consider supporting our mission.